Adventure on Hinchinbrook Island – A 1953 Bushwalking Account

In January 1953, six members of the UQ Bushwalking Club braved storms, leeches, and cliffs to climb Mt Bowen and traverse Hinchinbrook’s rugged peaks. Their rain-soaked success captured the spirit of early exploration on Australia’s “Skye” and left a legacy for today’s adventurers.

In January 1953, six members of the University of Queensland Bushwalking Club set foot on Hinchinbrook Island, eager to tackle one of Queensland’s most rugged landscapes. Their goal: to scale Mount Bowen, the island’s highest peak, and explore its dramatic ridges, cliffs, and wild coastline.

Australia’s “Skye”

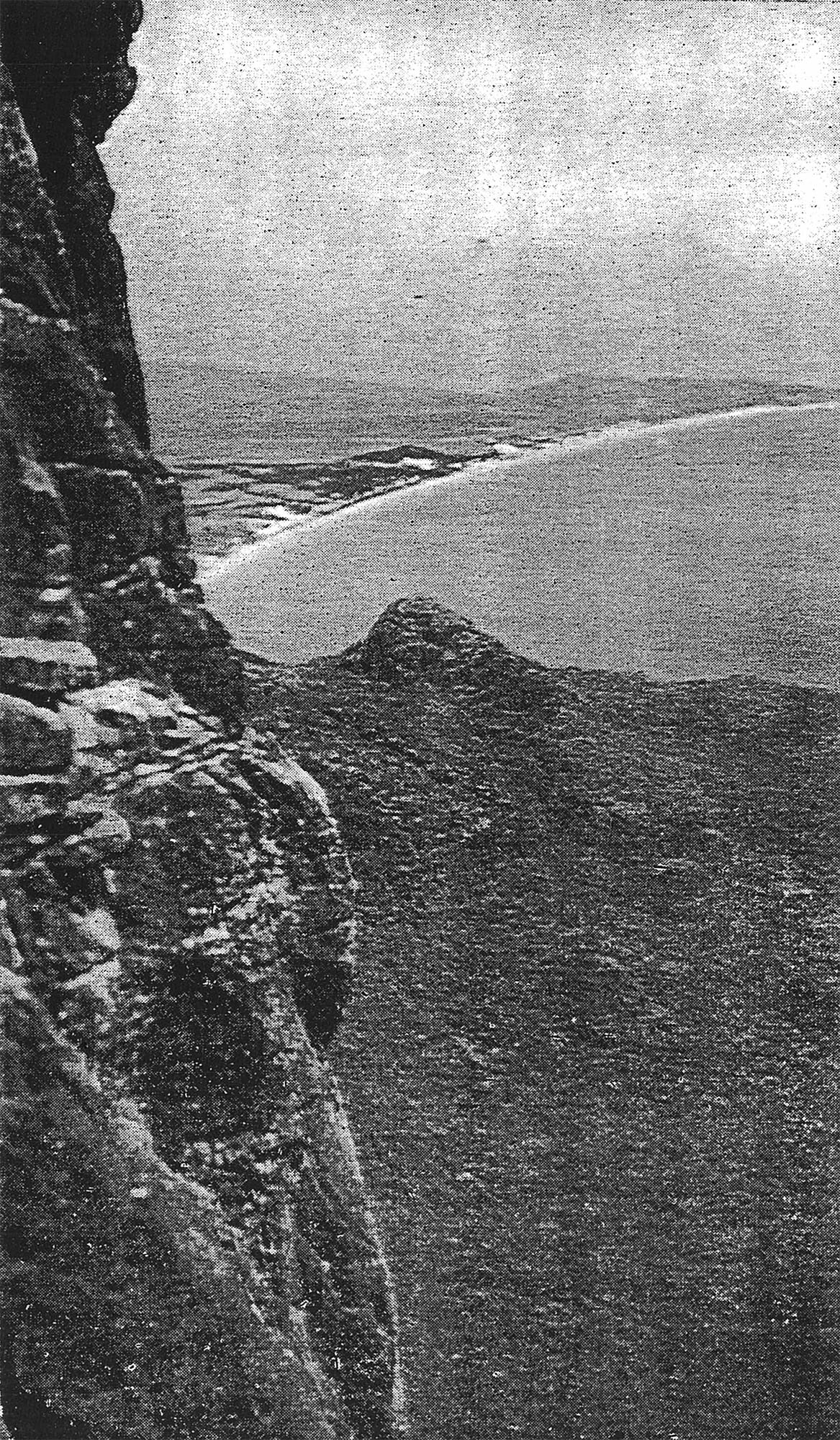

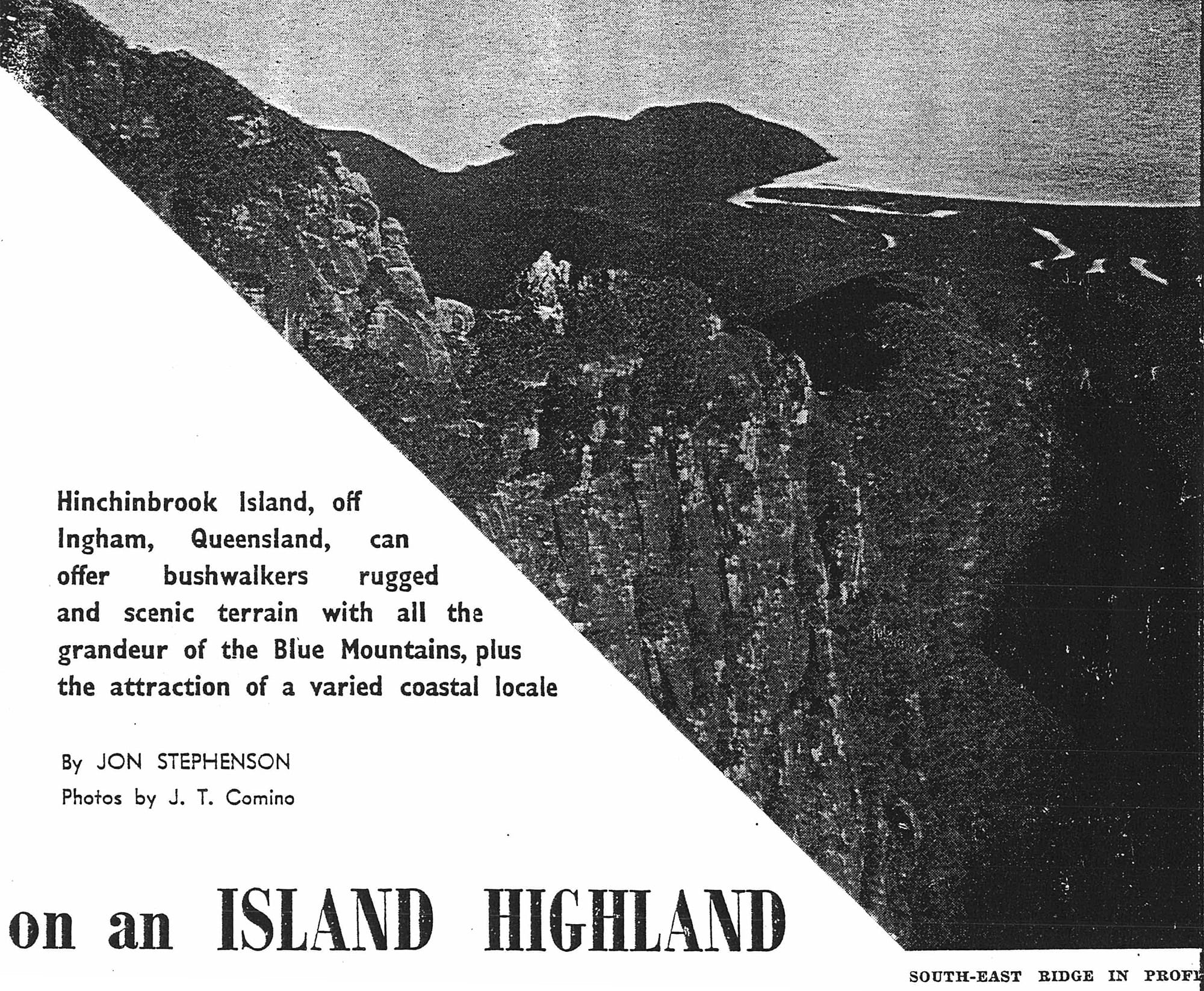

Hinchinbrook has long been described as a counterpart to Scotland’s Isle of Skye — a place of towering granite peaks, bold buttresses, and forbidding escarpments rising sharply from the sea. Stretching 30 miles in length, the island had been declared a National Park in stages between 1932 and 1941, but in the early 1950s it remained a frontier for adventurous walkers.

Bare granite dominates the landscape, with pinnacles and cliffs flanked by tangled jungle, mangroves, and coastal flats. Vegetation ranges from lush rainforest in the valleys to stunted banksia scrub on the windswept ridges. Uninhabited then (as now), Hinchinbrook presented both beauty and hostility — a challenge fit for the keenest bushwalker.

Early Ascents of Bowen

The first recorded climbs of Mount Bowen date back to the 1930s. Among the early pioneers were Roy Pearson, an Ingham cane farmer, and R.W. Lahey of Brisbane, who made their way up from Missionary Bay and the creeks on the island’s western side.

By the 1950s, Bowen was still considered a serious challenge, with its sheer cliffs and storm-prone weather. Several attempts by private and club parties had ended in retreat due to poor conditions.

The 1953 University of Queensland Expedition

Led by John Bechervaise, the University of Queensland Bushwalking Club made its attempt in January 1953, ascending the south-east ridge of Bowen. The party split into two groups, battling rain, humidity, and treacherous terrain. After days of arduous climbing and wet camps, they reached the summit ridge, where they were rewarded with sweeping views: east to the Coral Sea, west to the Herbert River valley, and north and south along Hinchinbrook’s jagged spine.

They traversed the Thumb, Diamantina, and Straloch, enduring heavy packs, steep rock pitches, and constant wet weather. Nights were spent under makeshift camps, battling leeches and discomfort, while days were filled with route-finding across cliffs, buttresses, and flooded creeks.

Trials and Triumphs

The party faced flooded rivers, fierce storms, and the constant threat of exhaustion. At times, progress was slow — battling through tangled rainforest, descending to fetch water, or forcing a route up near-vertical faces. Their persistence, however, paid off.

The climbers experienced Hinchinbrook in its rawest state: colourful beaches far below, cloud-draped ridges, and sunsets glimpsed through rain squalls. Their eventual success was a testament to endurance and determination.

Legacy

Today, Hinchinbrook remains a wild and revered destination for bushwalkers. The Thorsborne Trail (opened in the 1980s) offers a way to experience the island’s east coast, but Bowen and its satellite peaks still stand as serious undertakings, attempted only by experienced adventurers.

Looking back on the 1953 expedition, we see not only the challenges of climbing Bowen but also the spirit of exploration that has always been at the heart of bushwalking in North Queensland. For those who venture onto Hinchinbrook today, the legacy of those early climbers endures in every rugged ridge and rain-soaked camp.

Adapted from Jon Stephenson’s article in Outdoors and Fishing (November 1953), with photos by J.T. Comino.

- Luen